An exhausted Faye Dunaway savors the sweetness of breakfast and flashy newspapers, celebrating her triumphant Oscar win for Network the evening before. The iconic 1977 image, taken at the Beverly Hills Hotel, would become a testament to the industry’s transformation from its Golden age to the gritty aesthetic that defined a new generation. Dunaway’s own journey mirrored the very evolution of the film industry itself, a progression beginning in the States with Arthur Penn’s "Bonnie and Clyde," filmed in Dallas, Texas, just a decade earlier.

Dunaway, with her raw energy and unconventional beauty, became the embodiment of this new wave. She was the anti-movie star. Her lean, pre-heroin chic figure, big eyes, mesmerizing face, and unsettling demeanor was Hollywood without the glam, stripped down to its bare bones; Monroe and Dietrich and Hepburn and Crawford be damned.

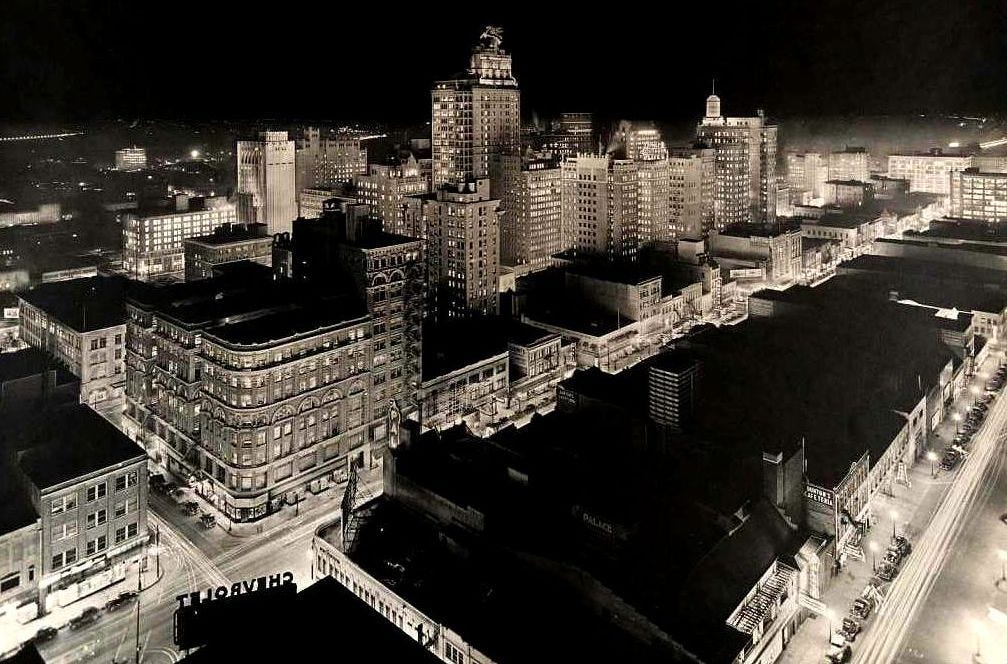

It's ironic, then, that the City that inspired the film, home to the notorious criminal couple, would be the one to kill Old Hollywood for good. To this day, Dallas still typifies, as I’ve said before, an amalgam of the gun-slinging Wild West and high-fashion glamor. It would be an understatement to say it was an unlikely source of revolution. Dallas was, in fact, an epicenter of anti-Hippie sentiment. And yet a re-telling of one of its most notorious tales would bring Hippie culture to the masses.

In the mid-60s, Hollywood was battling for survival. The studio system that had once been a well-oiled machine was breaking down — televisions in every home threatened to upend the system that protected a pantheon of stars that occupied a higher order, accessed only by trips to the Theater on larger-than-life screens and myths of glitzy stars from Garbo to Taylor.

Movies had become impossibly big—and impossibly expensive—in order to compete with television. Paramount's Cleopatra, despite its opulence and star power, nearly brought the studio to financial ruin. European art film, lightyears ahead of Big Studio pictures that had become machine-made products rather than singular artistic visions, offered alternative fare back home and inspiration for American filmmakers ready to buck the status quo in a rigidly conservative nation. Enter the 1967 hit, “Bonnie and Clyde.”

"They're young, they're in love, and they kill people," the film’s promotional materials read. Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, the notorious criminal couple on whose story the film was based, were products of Depression-era squalor. Dallas' own Robert Benton, co-writer of the film, was acutely aware of the societal backdrop against which Bonnie and Clyde's escapades had unfolded, but also the unraveling social order of the sixties which the film mirrored. Like the real-life outlaws it mythologized, the film threatened to upend the established order.

The film represented a departure from sanitized depictions of violence—its audacious portrayal of blood and death was as much a response to changing times as it was an artistic act of rebellion. It was also a reflection of the perceived tenacity and danger of Dallas, and by extension, Texas itself. The city of Dallas, like the criminals it housed, has always been an enchanting contradiction, marrying the allure of a bygone era with the unmistakable energy of the modern age. The same paradox was playing behind the scenes in Hollywood.

Released to a storm of criticism and derision by New York’s yuppie elite, the film would soon find an unlikely champion in Pauline Kael, a relatively unknown writer at the time for The New Republic. Frustrated by her editor’s refusal to publish her spirited defense of the film, Kael found an ally in the legendary William Shawn of The New Yorker. She felt "Bonnie and Clyde," which the New York establishment dismissed as lacking taste, was a mirror held up to the American public.

"When an American movie is contemporary in feeling, like this one, it makes a different kind of contact with an American audience from the kind that is made by European films, however contemporary," she said. “Our best movies have always made entertainment out of the anti-heroism of American life; they bring to the surface what, in its newest forms and fashions, is always just below the surface.”

Kael wasn’t shy about confronting those worried about violence on screen. She advocated for the freedom of artists to portray stories as they see fit, recognizing it as a tool for expressing deep, primal truths. The use of violence in "Bonnie and Clyde," as Kael suggested, was far from gratuitous; it was integral to the narrative, stirring the audience from complacency and challenging them to confront the realities of life.

In her iconic review, she recalled one audience member’s shock and dismay at what unfolded: “During the first part of the picture, a woman in my row was gleefully assuring her companions, ‘It’s a comedy. It’s a comedy.’ After a while, she didn’t say anything. Instead of the movie spoof, which tells the audience that it doesn’t need to feel or care, that it’s all just in fun, that ‘we were only kidding,’ Bonnie and Clyde disrupts us with ‘And you thought we were only kidding.’”

The real Bonnie and Clyde grew up in poverty in Depression-era Texas. Their paths crossed in January 1930 at a mutual friend's house. Bonnie was married but separated, and Clyde was a small-time thief with several run-ins with the law. Their immediate attraction set the stage for one of the most infamous partnerships in American criminal history.

For the next four years, Bonnie and Clyde, alongside their ever-changing roster of gang members, embarked on a violent spree of robberies and killings that spanned multiple states. From small-town gas stations and grocery stores to banks, no establishment seemed safe. Their brazen disregard for law and order made them figures of mythic proportion that echo to this day. (A few months ago, on a trip to London, I walked by a theater near Trafalgar Square advertising a Bonnie and Clyde musical.)

Their escapades fueled sensational newspaper fodder when the nation was in dire need of distraction. Framed with a perverse sense of glamor, public sentiment began associating their recklessness with a rebellion against a failed American system. Bonnie's role in the gang was particularly a marked deviation from the typical female stereotype, one that was captured brilliantly by Dunaway’s portrayal some thirty years later.

Bonnie Parker, who herself had dreams of stardom, saw her posthumous fame explode once again with the release of the film. Thousands attended her real-life funeral, and thousands more experienced her rebirth on screen. Even today, the impact of the crime spree resonate throughout Dallas, from a small historical plaque in Oak Cliff to a bank-turned-roadhouse—the ‘Gar Hole’—that the pair once robbed, to the still-standing burger joint in East Texas where they once dined. I grew up mere minutes from their grave sites.

One can argue that the mythology of Bonnie and Clyde was shaped more by the press and public imagination than by their actual deeds. The infamous picture of Bonnie with a cigar and a gun, a picture she reportedly posed for as a joke, would become one of the most enduring images of the pair, cementing their image as the wild, reckless outlaws of Texas.

The mythology of Bonnie and Clyde encapsulates the paradox of Texas, a state that values order and conservatism yet celebrates the outlaws who defied those values. Their story intertwines with the narrative of Texas as a land of risk-takers, rebels, and pioneers who chose their own paths, even if it led them outside the bounds of the law. The memory of thier grotesque criminal escapade is now an indelible part of Texas history and American popular culture.

The iconic story would become a perfect metaphor for the social milieu of the mid-sixties in America. The astounding success of the film proved Kael right — and served not only as a testament to the American public's enduring fascination with the notorious couple but as a rallying cry for the brewing counterculture.

The film was not without its creative liberties. For instance, Frank Hamer, the respected Texas Ranger who tracked down Bonnie and Clyde, was controversially portrayed as the movie's spiteful, revenge-seeking villain, a stark contrast to his revered real-life persona, which was portrayed respectably by Kevin Costner in John Lee Hancock’s 2019 film, The Highwaymen.

Just as the real Bonnie and Clyde inspired a series of subsequent emulations, so too did the film. American films that went on to redefine the industry were made possible by the film’s success, including The Graduate, Midnight Cowboy, Klute, Play Misty for Me, Dog Day Afternoon, Medium Cool, and Mean Streets — as well as some other Texas-based flicks, from The Last Picture Show to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Pauline Kael summed up the reason for the influence of the film well: “Maybe it’s because “Bonnie and Clyde,” by making us care about the robber lovers, has put the sting back into death.” Near the end of the film, Faye Dunaway’s Bonnie reads a real-life poem written by the gunslinger:

“Someday they’ll go down together;

They’ll bury them side by side;

To few it’ll be grief—

To the law a relief—

But it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.”

And so it went. In the hot summer of 1934, it was death for Bonnie and Clyde. But in the summer of ‘67, it was death for Old Hollywood... ✭